Santa Fe Annex

|

After 1914: The white building in the foreground at 201 Rosenberg (25th) is the Santa Fe Annex, 8 floors, 1913, built to house the offices of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad’s Gulf Lines as well as the unified passenger depot for the several railroad lines converging there. Further back the 4-story brick Victorian Romanesque building at 119 Rosenberg (25th) was the previous Union Passenger Depot, 4 floors, 1897, missing the truncated 2 story crenelated tower which was taken off after 1914 (See 25th Street Pier showing the tower intact).

|

24 March 2019: 124 Rosenberg (25th): Shearn Moody Plaza (Santa Fe Building), 11 floors, 1932. The structure united the 1913 Santa Fe Annex on the south end of the street within a larger building with elements of the Art Deco style in the center block, and matched the Southern annex with a mirrored building on the north side. As the anchor building of Galveston’s Strand Street, it has long been the focus of the district.

|

|

Shearn Moody (1933-1996) was the scion of the Moody Family, one of Galveston’s most enterprising families. His grandfather was Colonel William Lewis Moody (1828-1920), a University of Virginia lawyer who first came to Texas in 1856 and settled in Fairfield, Freestone County where he went into business with brothers David and Leroy. When the Civil War began he organized and became the captain of one of the first companies in Texas. Company G of the 7thTexas infantry mustered into service Oct. 2, 1861 and joined the battle lines further east. Captain Moody was captured and made a prisoner of war, incarcerated for six months at Camp Douglas, Camp Chase and Johnson's Island. Moody was part of a prisoner exchange in September 1862, and the 7th Texas Regiment was sent to Clinton, MS where Captain Moody was made lieutenant colonel of the regiment. He was seriously wounded at Jackson, MS on July 19, 1863, then promoted to a full Colonel and assigned to post duty at Austin, TX, where he remained until the end of the war. In 1864, he came to Galveston and established a cotton factorage business, W. L. & F. L. Moody. He entered politics and was elected to the reconstruction legislature of 1874-1875, and later appointed by the governor as financial agent of the state of Texas. In his capacity as chairman of the Galveston deep water committee, he spent much of his time in Washington in 1882 in the interest of the development of a deep water port on the Texas coast. Back in Galveston he organized the Galveston Cotton Exchange, and served as its president for many consecutive terms. At his death in 1920 he was president of the banking institution, W. L. Moody & Co., as well as the Galveston Compress and Warehouse Company and the W. L. Moody Cotton Company.

|

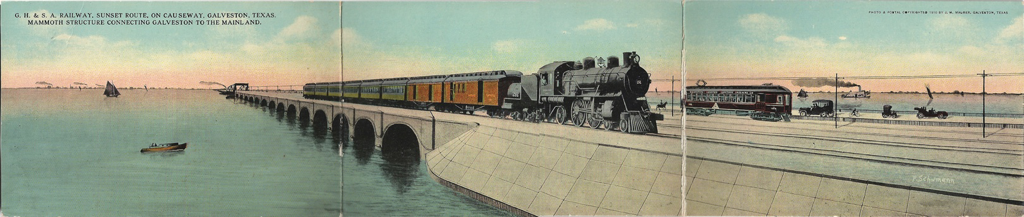

Colonel Moody’s son William Lewis Moody, Jr. came to control much of the family wealth after the death of his father. In 1942 he and his wife Libbie Rice Shearn Moody incorporated the Moody Foundation, a philanthropic organization which continues to promote education, social services and community needs. Libbie was the granddaughter of Charles Shearn (1794-1871), an Englishman who came to Texas in 1834 and fought in the Texas Revolution. Coming to Houston in 1837, he became a prominent businessman, served 6 years as Chief Justice of Harris County, and founded a Methodist Church which would come to bear his name, Shearn Methodist Church. The Moody Foundation bought the Union Station Building in 1976 and rehabilitated it to include one of the largest railroad museums in the US established to educate the public about the role of railroads in development of the island economy. The Sante Fe Building was renamed Shearn Moody Plaza to honor the grandson of William Lewis Moody, Shearn Moody (1933-1995), who would soon be featured on the cover of Texas Monthly as "the sleaziest man in Texas." From his youth Moody had been widely known for his unconventional and even bizarre behavior, eccentricities which included building a slide from his bedroom window to a swimming pool where he kept pet penguins, wearing house slippers wherever he went, and throwing wild parties at his west Galveston Island ranch. After a decade-long investigation, Shearn was convicted of bankruptcy fraud in connection with misappropriation of Moody Foundation funds, and was sentenced to 5 years in federal prison. He served little time and was released on parole in 1991, after which he led a reclusive life with his long-time partner, Jimmy Stoker, a former dancer and choreographer from Las Vegas. In his last years Shearn developed Moody Gardens, a theme park and Rainforest Pyramid which became a popular attraction to the city. Shearn suffered from chronic high blood pressure and kidney disease and received regular dialysis treatments before his death in 1995 at his parents home. Jimmy Stoker had to resort to a lawsuit to obtain control of the ranch he had been promised.

|